Modern liberal democracies cannot succeed unless governments appear competent. If voters don’t believe that the politicians they elect are capable of running the show, they’ll lose faith in the system. The risk of a crisis of confidence in democracy drastically increases, examples abound.

The need for competence in government is complicated by the fact that democracy is a messy business. It’s premised on the notion that just about any preference expressed by a voter or organized interest group can and should play a role in influencing the behavior of the government.

Obviously, that isn’t necessarily a bad thing, and we often have pretty good ways of navigating this constellation of interests. At the best of times, democracies actually are governed more competently than authoritarian or semi-democratic regimes, but that web of competing interests can tie legislators in knots, making it seem like our government is good for nothing.

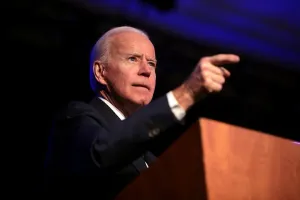

This unfortunate reality is on full display in the legislative mess of Joe Biden’s year-old administration. His Build Back Better legislation (BBB) is in trouble. What was advertised as a “transformative” set of policies to enhance the United States’ anemic social safety net and battle climate change has shrunk, mostly because of the objections of moderate Democrats like West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin. Now eight months later, without the passage of even these downsized proposals, Joe Biden looks unable to deliver the competent government and “return to normal” that he promised.

Democratic messiness isn’t the only reason that BBB hasn’t passed thus far. Organized and wealthy interests want to avoid the tax increases that are part of the bill, or the half-trillion dollars that it would spend on climate. One can look at oil companies’ recent big donations to Joe Manchin for an example. This helps explain why the bill’s scope has shrunk.

But in the immediate term, messiness is the problem. What remains of the initial Build Back Better legislation is a patchwork of underfunded and poorly planned policies. But interests within the Democratic Party—from single-policy-focus non-profits, to legislators with longstanding pet policy priorities—know this may be their last chance. That makes passing a bill which focuses on quality over quantity all the more difficult.

It’s natural that in a liberal democracy interest groups and legislators, even when loyal to the same political party, will have disparate goals. That’s just how democracy works. But American democracy is undergoing a crisis of confidence. One of its two political parties is increasingly capable of winning political power without popular majorities and increasingly eager to dispute election results when it loses. It’s quite important that the other party shows that democratic government can, in fact, work.

If that means going back to the drawing board on BBB and picking one or two policies to design and fund well (in addition to its major climate spending, which is a necessity) then Democrats should do that. If they instead pass a patchwork bill full of weak policies that don’t really improve the lives of citizens, then democracy’s tendency towards messiness will have gotten in the way of competence. In these troubling times, that could be disastrous.

Subscribe to Spectacles

Comments

Join the conversation