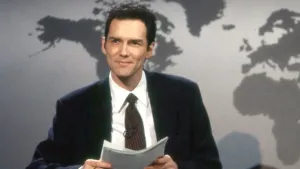

Only five days ago, on September 14, comic legend Norm MacDonald passed away. Let me first disclaim this article is not really about Norm MacDonald’s style of humor or his legacy as a comedian. That is for many reasons, the first of which is that I simply don’t know enough about the man or his life. I didn’t actually know all that much about Norm MacDonald until a few months ago, when YouTube decided it was time to show me some of his Weekend Update highlights.

Sad or strange as it may be that my—and I imagine many of my peers’—cultural awareness is shaped by this kind of algorithmic happenstance, I am lucky to have been made to stumble upon him when I was. I spent the next couple months watching just about every Norm video I could find on the internet, laughing along as he frequently laughed at his own jokes. I had no idea that all that time the man I was laughing along with was quietly struggling for his life, and since his passing I have thought a lot about what comedy is and what made his particular brand so belly-achingly hilarious. But, as I said, this is not about Norm’s comedic style. Instead, this is about a moment of reflection, brought to my mind in the wake of his untimely passing, about the role of comedy in a democracy.

When the subject of humor and politics arises today, it’s hard not to think of our recent president, Donald Trump. Regardless of what you think of his political behavior, he might just be the funniest president we’ve had, even in spite—or perhaps because—of the fact that he was so perpetually ludicrous and embarrassing.

It’s hard not to laugh at a sitting US president exclaiming online, “As I have stated strongly before, and just to reiterate, if Turkey does anything that I, in my great and unmatched wisdom, consider to be off limits, I will totally destroy and obliterate the Economy of Turkey (I’ve done before!).” The absurdity of boasting of his “great and unmatched wisdom” is not much different from his looking up at the sky while talking about Chinese tariffs and declaring, “I am the chosen one.”

As absurdly humorous as the man may be in his own unique way, his off-teleprompter rambling and social media outbursts often left me with a nagging sense that something wasn’t quite right. On the one hand, he was funny and easy to laugh at. On the other hand, he was, after all, the President of the United States, and that made the humor sting in its own peculiarly painful way. It felt good to laugh at something which felt laughable, but it also felt wrong, because this thing I was laughing at—the President—is not supposed to be laughable or absurd but competent, intelligent, and reassuring. And this torn feeling was only amplified by the fact that right alongside some funny tweets sat casual threats of nuclear war, declarations of policy that could crater global markets, and, perhaps worst of all, the ginning-up of fantastical conspiracy theories which reached their highest manifestation in the January 6th insurrection. Funny as he was, he was also dangerous. Yet there I was and am, laughing away.

This contradiction of feelings, the confusion that absurd humor can generate, is obviously not limited to Donald Trump or the actions of political figures. It’s prevalent in just about all American political satire. Take Saturday Night Live, for instance. Now, you may be thinking, “I thought we were talking about funny stuff,” but just hold on. Whether it was Tina Fey’s idiotic Sarah Palin, Kate McKinnon’s ambitious and cold Hillary Clinton, or Alec Baldwin’s bombastic Donald Trump, SNL has done a halfway funny job skewering a lot of politicians in recent years.

The trouble with this kind of political comedy is that it can, in a way, mask the horror. Baldwin’s impression of Trump may have been hilarious, but it made humorous what was really quite objectionable behavior from a president or presidential candidate: endorsing conspiracy theories that a John McCain or a Mitt Romney never would, threatening to jail a political rival in a debate, and so much more. When politics are relatively stable and decent, there’s no harm in, as Tina Fey described it, “goof”ing on politicians, but in other times, comedy can fail to seriously confront dangerous situations.

This is a problem Malcolm Gladwell highlighted in 2016 on his podcast, Revisionist History. In the episode, “The Satire Paradox,” he criticized this kind of humor for being toothless, lame, and cowardly. In his words, real satire “uses a comic pretense to land a massive blow,” and as an example he cites the Israeli program, “Eretz Nehederet” or “A Wonderful Country.” The sketches he describes are brutally dark in their satire about the violence the country has embroiled itself in, and he claims this is the kind of satire America needs. The bleakness of the show is rooted, he says, in the country’s violence which allows for this kind of confrontation.

But, as he explains where this satire comes from in Israel, he seems to forget just how inapplicable to America this expectation is. Israel is a violent place—the reasons for which will not be explored here. The kind of heavy-hitting satire that strikes deep in people’s hearts is not so common in America, because of the general prosperity and domestic peace America has achieved since the end of World War Two. It takes a traumatized people to generate the kind of traumatic satire which hits hard and really confronts the terrors of our world not merely as jokes but as funny, though indeed terrifying.

Gladwell claims simple laughter at our problems is an inadequate and cowardly response. In a way, this feeling—that to laugh at our problems is in some way reprehensible—is perhaps at the core of much of political correctness. There is a desire to halt humor at the threshold of seriousness, when humor becomes offensive in its failure to recognize the gravity of some given situation. Political correctness is born out of a similar sentiment to Gladwell’s: that serious things should be treated seriously and that to do otherwise is cowardly. I have to disagree. To laugh at the absurd or the horrifying things over which we feel we have no control is a perfectly normal human response, and different cultures and people have different ways of coping.

According to Plato, one of the most astute observers of the human condition, Socrates said, “when a man lets himself go and laughs mightily, he also seeks a mighty change to accompany his condition.” Now, it was also said by the ancient Greeks and by Aristotle—and is said today—that tragedy offers catharsis, or the purification of one’s emotions by releasing pent-up feelings. When we cry at the end of a tragic film, the experience of anguish allows us to release whatever sadness we had been bottling up for who knows how long.

Comedy offers another sort of catharsis, as Socrates points out in his own somewhat cryptic way. When it comes to political satire or laughing at Donald Trump’s embarrassing lack of self-awareness, I do find that nagging feeling points in the direction of Socrates’s observation. When we see things like that tweet above from the president, it’s understandable to feel aghast and wish things could be different, and it’s equally understandable to laugh, disarmed from the knowledge that nothing you can do can change the way he is or the fact that he sits in the oval office.

Comedy, like tragedy, is a release valve for pent-up anxiety, discomfort, and even sadness. In a democracy, yes, we can vote; and, yes, we can be activists; and, yes, we can work to get people to do those things too. And, yes, we should do all those things when the time is right.

But we also have the immense privilege of being able to laugh and poke fun at anyone and anything. That, too, is something we ought to do, because it makes us feel some bright moments of satisfaction, happiness, or catharsis in times which could otherwise be oppressively dark.

In our society founded on secularism and individualism, not only do we have the First Amendment. Here, nothing is sacred. Anything can be the butt of a joke, except, that is, those things decided by the people to be off-limits. One is reminded of the political correctness discussed above.

At the beginning of this article, I lied to you. Well, misled you. This article isn’t about Norm MacDonald’s style of comedy, but it is, in a way, about his apparent approach to life. That approach, which showed itself in Norm’s comedy, was an absolute and total disregard for what other people thought or expected of him. In interviews and late night talk shows, Norm would intentionally derail conversations, laughing at his own joke of making a complete mess of expectations and decorum. As I’ve written before, in a democracy, everything is political, and when we laugh mightily with Norm MacDonald, in certain ways we are desiring similar changes as when we laugh at Donald Trump.

As people, we strive to be independent, to be like Norm and care not a whit what anyone else thinks about us. We want to have pride in ourselves, and we want the old adage to be true, that sticks and stones will do the damage that words or the opinions of others never could. And yet, as we live in a democracy in which everything is decided according to what “everyone else” thinks or believes, we are forced to care about the opinions of others. When we laugh at Donald Trump, we desire a great political change of a kind. When we laugh at Norm MacDonald, we long for another: a liberation from the expectations and prejudices of others, not unlike the liberty Norm seems to have uniquely possessed in spades.

He is also a reminder of just how wrong Malcolm Gladwell and other terminally-humorless people are. Even in the midst of his silent battle with cancer, Norm found humor, laughing at his own ridiculous, drawn-out bit of poorly live-tweeting sports games to everyone’s chagrin. In our democracy’s dark moments, it serves as a reminder not to take ourselves too seriously and to find the time and the opportunities to laugh at ourselves or whatever we can.

The answer is not to laugh at all things at all times. There is a need for sincerity and genuine desire to improve our world and fix our problems. But if all you can do is that, if all you can be is severely sincere at all times, if you cannot find the moments to laugh at yourself or the things which scare you, you will not die a happy person. As successful as you might be in fixing problems or helping people, you may save many but lose yourself.

Subscribe to Spectacles

Comments

Join the conversation