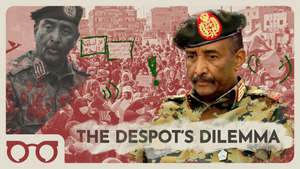

Three years ago, the people of Sudan successfully ousted longtime military dictator Omar al-Bashir and started their country on a path to democracy. Today, though, things look grim—a new military junta has blocked the democratic transition and rules repressively from Sudan’s capital, Khartoum. But why did the new leadership reverse course? Its refusal to cede power is part of a larger political trend of violent dictators who would rather stay in power than flee to comfortable exile. We explore why and find an uncomfortable and surprising answer. Watch now to learn.

Transcript

This is Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok at his lowest point.

In January, he announced his resignation, warning his country was on a dark path. It was a less than subtle remark on the Sudanese military’s stubborn refusal to share power with civilians.

Hamdok certainly tried his best to find common ground; just months earlier the military had placed him under house arrest — “for his protection” they said. Since 2019, when popular protests ousted the former dictator Omar al-Bashir, the military’s been rebuilding its political power, waiting for this moment.

You may think that’s business-as-usual for militaries and dictators, but things weren’t always this way. In the past, brutal despots under enormous pressure to surrender frequently fled their countries, living out the rest of their days in comfortable exile. In 1998, though, something happened. Violent dictators just don’t give up like they used to.

So, what happened in 1998? And why won’t Sudan’s military hand over power?

The answer reveals a deeper dilemma about how to balance justice and progress, not just in Sudan, but anywhere.

When Omar al-Bashir and his allies overthrew the democratic Sudanese government in 1989, they inherited a fragmented, fragile state. In the country’s hinterlands, a complex network of armed groups vied for power, with some in open rebellion and others aligned with the government. Bashir weaponized Sudan’s insecurity and instability to consolidate and grow his own position, eliminating political rivals in the capital of Khartoum and forging alliances with powerful militias on the periphery.

By 2000, he had sidelined his allies and established a pyramid of violence with himself at the apex. The most infamous of Bashir’s crimes was a brutal genocide in the Darfur region of Sudan. In 2004, Arab militias, politically dominant and empowered by Bashir’s militarism, Murdered and starved as many as 300,000 non-Arab Darfuri people. Exact numbers are unknown but more than 3,000,000 may have been displaced.

Bashir, of course, was heavily implicated, despite not being directly involved. And while armed violence calmed down to some extent in the years following Darfur, Bashir had a problem. You see, in 1998, while Bashir was consolidating his hold on power, 120 countries voted to adopt a groundbreaking treaty—The Rome Statute— establishing the unprecedented “international criminal court.” Its mandate: to bring to justice perpetrators of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crimes of aggression— in other words, to prosecute men like Omar al-Bashir. In 2009, he officially became a wanted man.

Yet the looming threat of the International Criminal Court wasn’t Bashir’s only problem. In 2011, Sudan’s economic powerhouse — the oil-rich southern region — seceded to form the nation of South Sudan. Surprisingly, this was pretty bad for Sudan’s economy, which shrunk nearly 11 percent. By comparison, US GDP dropped a mere two and a half percent in the Great Recession.

After seven years without its oil, Sudan wasn’t exporting nearly enough to pay for critical imports like food and fuel. In 2018, its currency imploded, and Sudan’s economy collapsed almost completely. Overnight, the price of bread tripled, and hunger spread. By December, protests had erupted across the country. Bashir’s government responded with a mix of repression and empty promises of reform, but the writing was on the wall.

On April 11, 2019, military leadership finally grasped the depth of the crisis and ousted Bashir. Dissatisfied with yet another military government, the Sudanese people persisted in their peaceful agitation. For nearly two months, civilian leadership negotiated with the military… until on June 3, the military opened fire on civilians in the capital.What followed would become known as the Khartoum massacre. Estimates place the death toll in the hundreds. Dozens of bodies were dumped in the Nile River.

Still, the Sudanese people refused to give up their fight for freedom and democracy. Eventually, the junta relented and agreed to a government led jointly by the military and civilians until the country was prepared to elect its own leadership—within three years. After thirty dark years of brutal repression, the Sudanese people glimpsed a light not seen since 1989. They had finally won.

But what, exactly, had they won?

Besides a path to democracy, the joint government improved Sudan’s standing in the international community, made peace with a number of prominent armed groups, and started—even if barely—to get skyrocketing prices under control. But all of those triumphs were modest at best. On the other side of the balance sheet, the military remained the de facto political power, a hindrance to reform rather than a willing partner.

Consider the post-revolutionary treatment of Omar al-Bashir. Bashir was sentenced to two years not in prison but in a rehabilitation center, not for genocide or crimes against humanity but for corruption. It’s hard to say exactly why Bashir hasn’t faced punishment for Darfur according to the 1998 Rome Statute’s rules, but it’s probably because many of his coup-makers were also responsible. For one, Bashir’s de facto successor, General Abdel Fatteh al-Burhan was stationed in Darfur during the genocide and was a principle leader during the Khartoum massacre.

Now, the military seemed to offer their stamp of approval when civilian officials agreed to hand Bashir over to the ICC, but, after they put Abdalla Hamdok under house arrest and dismissed the other members of the civilian cabinet just a few months later, one wonders whether they were being totally honest. Regardless, Bashir is still in Sudan, not in ICC custody; Hamdok has left the government—permanently, it seems; and the military is still calling the shots, hanging on to power even in the face of energetic and sustained protests.

The reason Sudan’s military has clung so tightly to power is something we like to call “the despot’s dilemma.” It goes like this —

You have a situation in which those in power peddle violence with impunity, like in Sudan in the 90s and 2000s. So, outside international powers like the UN or a coalition of countries, try to craft “international law” to bring some accountability and reduce the bloodshed, as happened in 1998 with the Rome Statute. But paradoxically, this raises the stakes for those leaders who’ve broken the rules and committed some heinous crimes.

If they lost power before, they could just flee without worry, comfortably living off some pocketed portion of the treasury. Now, with rules and the threat of punishment, men like Bashir and other Sudanese commanders can’t tolerate a loss of power, because it could mean prison for the rest of their lives. So they fight tooth and nail — like cornered cats — to stay in power, even when their time is clearly up As a result, their body count just keeps rising, as they lash out with violence to repress those who threaten their safe perch.

Of course, rules like the 1998 Rome Statute do have a purpose. The threat of accountability can discourage excessive violence among those who haven’t yet perpetrated it, and international courts like the ICC have brought some terrible people to justice, including, just months ago, one of the criminals of Darfur. But on some level, if you want to see progress in a place like Sudan— progress toward democracy, away from military rule and despotism— those despots need off-ramps, ways out, golden parachutes, so to speak—guarantees that they’ll be okay.

In their effort to reclaim their nation, the people of Sudan face a tremendous challenge in the despot’s dilemma…a challenge that demonstrates two key ideas. First, even the best intentions behind efforts to craft international law can create perverse incentives that may intensify rather than reduce violent despotism. And second, despite those international efforts, it’s ultimately up to the people on the ground—whether in Sudan, in Myanmar, in Syria, or elsewhere—to make the tough calls, striking a balance between justice and progress, to chart their own path toward democracy, however messy and unjust that may be.

Sources

Core Sources:

Sudan: The Failure and Division of an African State by Richard Crockett

“Should I Stay or Should I Go? Leaders, Exile, and the Dilemmas of International Justice” by Daniel Krcmaric in The American Journal of Political Science

— — — — — — —

00:30 — “Sudan’s PM detained ‘for his own safety’” via The Guardian

00:50 — “Should I Stay or Should I Go? Leaders, Exile, and the Dilemmas of International Justice” by Daniel Krcmaric in The American Journal of Political Science

01:25 — “Military Coup In Sudan Ousts Civilian Regime” via New York Times

01:40 — “A.C.L.E.D. Conflict Data”

02:20 — “UNSC Report on Darfur”

02:35 — “Uppsala Data Conflict Program”

02:50 — “Nations Agree to Create Court to Try War Crimes, Despite U.S. Objections” via Wall Street Journal

03:00 — Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

03:10 — Al Bashir | International Criminal Court

03:35 — “GDP Growth” via World Bank

03:45 — “Trade Deficit” via O.E.C.

03:55 — “GDP” via World Bank

04:00 — “Several Killed in Sudan as Protests Continue” via Al Jazeera

04:20 — “Sudan’s Bashir Ousted by Military” via Reuters

04:45 — “Khartoum Massacre” via New York Times

05:00 — “Sudan: Military, Civilian Power-Sharing Deal” via New York Times

05:25 — “Sudan Removed from U.S. Terrorism List” via NPR

05:30 — “Sudan: Government, Rebels Sign Peace Deal” via Reuters

05:35 — “Sudan Improving From Situation of Shortages” via Al Jazeera

05:40 — “Sudan Freedom Score 2017, 6/100” via Freedom House

05:43 — “Sudan Freedom Score 2020, 12/100” via Freedom House

06:00 — “Bashir’s Punishment” via New York Times

06:35 — “Sudan Closer to Handing Over Ex-Dictator” via New York Times

06:40 — “Sudan’s PM detained ‘for his own safety’” via The Guardian

06:45 — “Sudan’s Burhan Dissolves Government” via Reuters

07:05 — “Energetic and Sustained Protests” via Reuters

08:40 — “Radovan Kardzic Convicted of Genocide” via New York Times

08:45 — “Darfur Suspect Appears before I.C.C.” via U.N. News

Comments

Join the conversation