Yesterday, President Joe Biden kicked off his long-promised “Summit for Democracy,” a (virtual) meeting of democratic—and, as it turns out, not-so-democratic—world leaders, along with pro-democracy members of civil society. The Summit’s stated goal, in Biden’s own words, is to,

lock arms and reaffirm our shared commitment to make our democracies better; to share ideas and learn from each other; and to make concrete commitments of how to strengthen our own democracies and push back on authoritarianism, fight corruption, promote and protect human rights of people everywhere. To act. To act.

To that end, the Summit is focusing on three main issues: authoritarianism, corruption, and human rights. Throughout his campaign and the first year of his presidency, Biden has framed America’s future as a contest between its highest democratic aspirations and emergent authoritarianism. International politics has been presented in similar terms, as a contest between the world’s liberal democracies and authoritarian countries like China. Concerns over corruption and human rights violations naturally follow from the possibility of an increasingly authoritarian world.

This summit, then, is so far up our alley here at Spectacles that it would be absurd not to cover it. At the same time, finding some discrete headline and breaking it down—our typical approach to Insight—risks missing the forest for the trees. For that reason, I want to take a bird’s eye (ha. ha.) view of the Summit’s goals and proceedings, offer some commentary, and connect the subject matter to past Spectacles pieces. Hopefully it brings home just how intimately interconnected the issues that we discuss are.

Now, most liberal democratic nations are experiencing their own brushes with incipient authoritarianism, although how well each is dealing with that problem varies. So, it’s not particularly groundbreaking for world leaders and members of civil society to acknowledge the obvious. But there are potential benefits in getting influential global actors into the same room (or Zoom call) to talk about it.

In a recent Bird’s Eye episode on the future of global peace, Philip and I discussed how providing forums for leaders to interact and hash out issues can facilitate real confrontation of shared challenges. The Summit for Democracies lacks certain advantages—which we discuss in that episode—of a proper international institution, but more summits could follow in coming years and incentivize leaders to demonstrate their commitments to democracy-bolstering reforms. Indeed, this inaugural meeting is supposed to be the starting point for a “year of action,” although it’s as-yet unclear how ambitious that year will be.

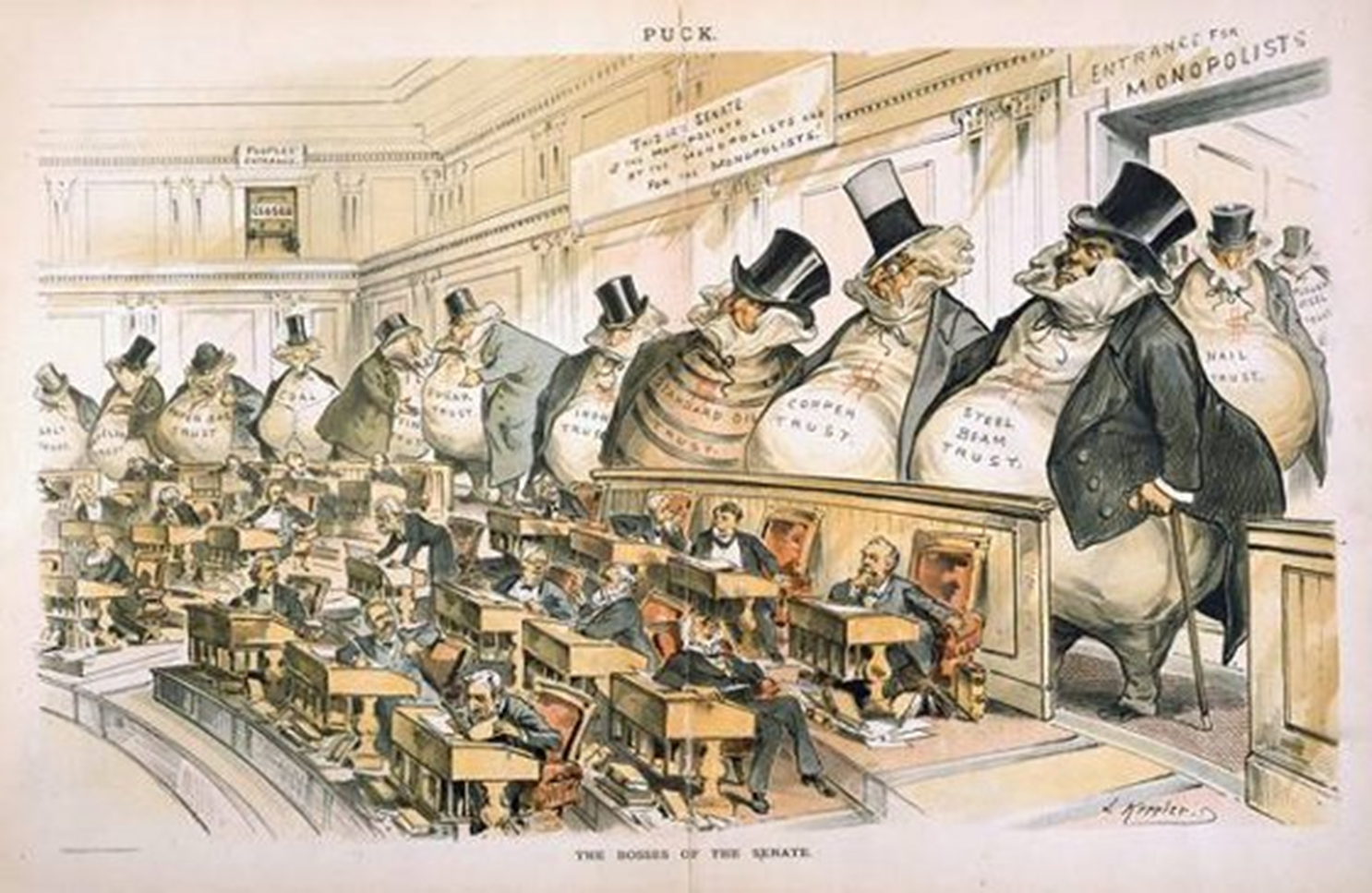

Another potential accomplishment could be real policy developments on the most concrete of the issues on the table for discussion: transnational corruption. Autocrats and kleptocrats habitually exploit lax rules of international financial regulation to squirrel away money and maintain a grip on the resources which keep them in power.

This is common in explicitly non-democratic countries as well as democratic ones where corrupt elements are effectively legalized, something we’ve covered in Bird’s Eye and in a recent Insight by Philip. Transnational corruption simply can’t be ameliorated entirely at the domestic level, so any movement towards international cooperation that sets out a clear agenda would be a major coup for the Summit (the good kind, that is).

That said, the Summit faces long odds on one of its other major goals: confronting authoritarianism. As much as Joe Biden wants to frame the near future of world politics in terms of an ideological struggle between democracy and authoritarianism—and as much as elements of the political commentariat are happy to oblige him—both American hypocrisy and the cold, hard demands of geopolitics give the lie to that kind of framing.

For example, the United States invited both India and the Philippines to the Summit. US foreign policymakers view both as key allies in its escalating competition with China, but India has seen its democracy decline precipitously in recent years and the Philippines’ president, Rodrigo Duterte, is one of the world’s most notorious human rights abusers. And even as Biden admits that the United States is not perfect, it’s more than a little bit telling that the US is in the process of completing a $650 million arms deal with Saudi Arabia, an absolutist monarchy fighting to maintain local hegemony on the Arabian peninsula, as the Summit kicks off.

The fact of the matter is that even as democratic decline is taking place around the globe, it is primarily the failings of democracy at home that have driven the democratic recession. There’s a limit to how much global maneuvering can rectify the problem. Focusing too much on international solutions, especially where clear policy prescriptions are lacking, is not going to produce the kinds of domestic democratic course corrections that are so desperately needed.

The Summit for Democracy still has promise, even if its lofty aspirations may fall short. It can facilitate solutions to democracy-related issues best addressed in the international sphere. Clarity about the shared challenges faced by the world’s democracies is always welcome, and a forum (especially if the Summit becomes a regular gathering) involving a diversity of key actors can complement domestic efforts. But it’s important to remember that international gatherings and agreements like this are only useful insofar as domestic policies follow suit.

Subscribe to Spectacles

Comments

Join the conversation