Just the other day, Derek Thompson published a piece in The Atlantic titled, “Why America Has So Few Doctors.” While the piece is generally quite good, I’ve got a couple problems with it. The first is that I was also planning on writing an Insight explainer about this exact topic, but now my thunder is stolen. Not cool, Derek. The second, and more important, issue is that Derek wrongheadedly seems to ignore a critical lesson about democratic functioning.

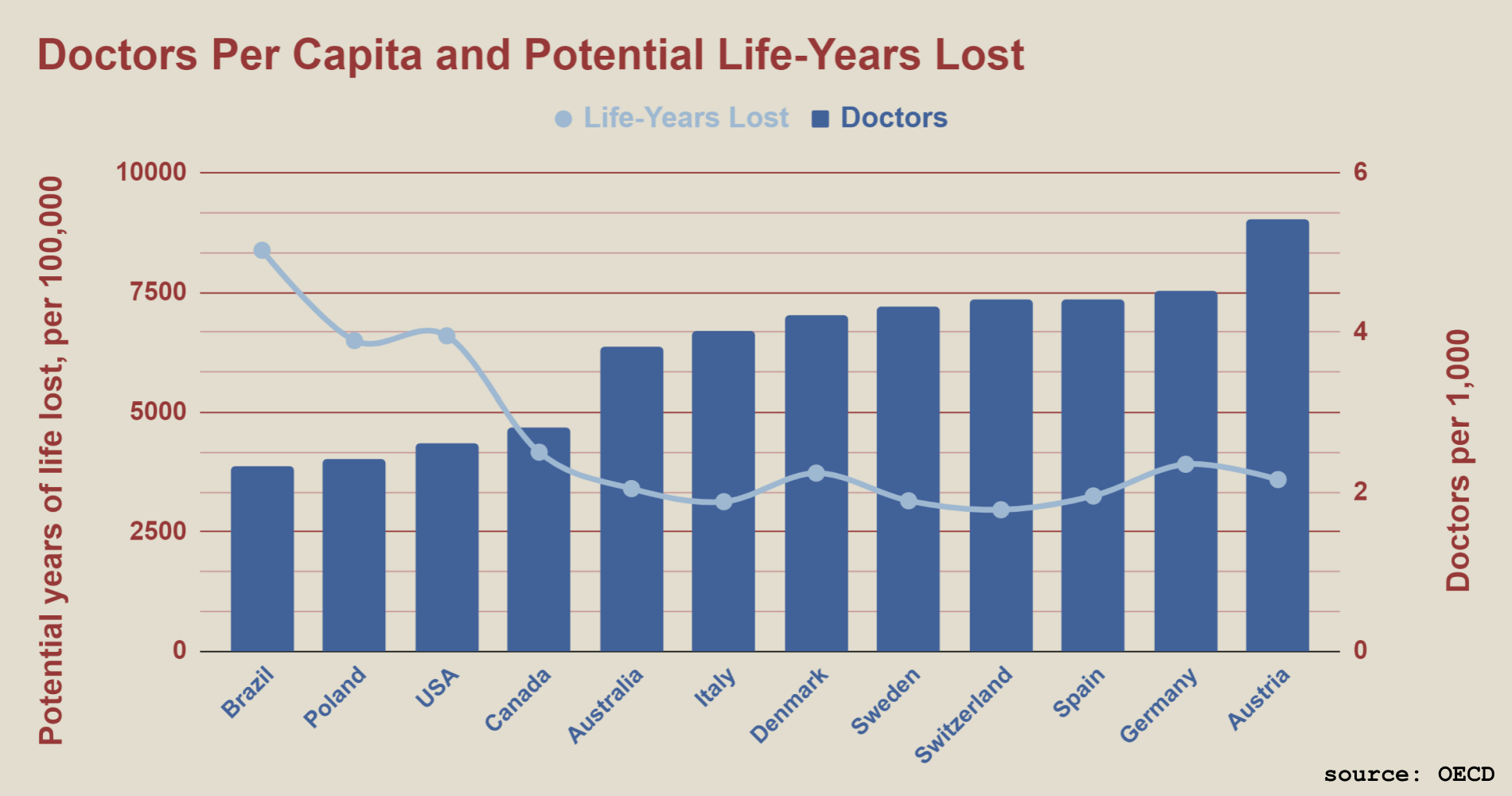

Before I get into that, however, I’ll quickly go through the ‘explainer’ portion of this subject—why America has so few doctors. To that end, it’s important to first note that we do in fact have a problem of doctor scarcity: less than half as many per capita as Austria, and 40% fewer than Spain, to name a couple. We lose twice as many expected life-years than the Spanish.

When you’re trying to explain low supply of any kind of manufactured good, you take a look up and down the production process to identify bottlenecks. In the case of doctors, the most serious bottleneck is in the quality control department: residency limits. The number of spots available for medical school grads to complete their training in hospitals is woefully low, thanks essentially to an act of Congress from 1997 which set the low ceiling.

If you want more detail, you can read Derek’s (much longer) explanation, but I’d warn you to be wary of the piece’s conclusion. In it, Derek offers a simple solution of increasing residency funding from the government, so we can train more doctors, but then he seemingly uncritically presents two potential “downsides” to this solution: student debt no longer covered by falling wages and lower quality medical care.

Whenever taking a look at a big problem and offering a seemingly simple solution, as Derek has, one must either admit there’s a “catch” or risk being seen as a starry-eyed fool. But pointing out these “downsides” to the solution is the wrong way to admit to a “catch.”

First of all, the downsides aren’t as drastic as they seem. If medical wages fall, presumably fewer people will enter med school, forcing schools to cut tuition costs, but insofar as the student debt challenge is more complicated, Harry and I discuss this in more depth in our Reflection podcast. On the other hand, lower quality care shouldn’t be a concern, because high quality care is of little use when it’s so scarce that people can’t actually access it.

Instead, it demonstrates greater nuance and is a better service to readers to admit that the “catch” is that this may be a simple solution but not one easy to implement. Bills have been floated to do what Derek recommends, but they inevitably fade into obscurity. The reason for that is the same as for Congress’s original 1997 restrictions: a very strong medical lobby which has the sole priority of maintaining and raising wages for doctors. Scarcity, it turns out, is one hell of a drug for the profiteers.

The big lesson here is not one of how policies have upsides and downsides but one of how our democracy and the interest groups within it shape policy and our world. It’s nice to suggest that policy should change, but we also need to consider the environment in which that would take place.

Subscribe to Spectacles

Comments

Join the conversation