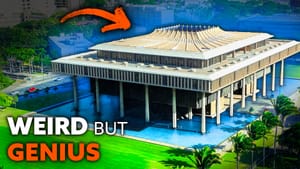

What is Hawaii? I’m here at the Hawaiian state capitol in downtown Honolulu — one of America’s most striking, and controversial state-houses. And it’s not just controversial because it ditches the dome and pediment and other Greco-Roman essentials of American political architecture; New Mexico, New York, and unfortunately Alaska already do that. It’s controversial because it’s supposed to represent Hawaii. And while there are a lot of really interesting, clever, and just plain cool things in this building’s design to express some essential characteristics of the islands, like the columns, the moat, the atrium, and more—which we’ll dive into in a second, I promise—to “represent Hawaii,” you have to have an answer to, “What is Hawaii?” But that’s more complicated than it seems.

To understand Hawaii’s oddities, you have to take a brief look at its history, and luckily it’s right across the street: ‘Iolani palace, the former seat of the Hawaiian monarchy, the only royal palace in the United States. Because from 1795 to 1887, Hawaii was a monarchy, that is until a coalition of wealthy, mostly white American, landowners forced the king at gunpoint to sign away his power. Despite attempts by Queen Lili’uokalani, the coup-makers, with help from America, held onto power and imposed literacy requirements on political participation, effectively disenfranchising native Hawaiians and hundreds of thousands of laboring immigrants from Japan, China, and the Philippines. In 1900, it was annexed by America, and for about half a century thereafter, Hawaii was basically just an oligarchy, ruled by foreigners who made fortunes off the land and labor of the islands.[1]

That is until after World War II, when things started to change. Veterans like Daniel Inouye, who’d fought for democracy in Europe, came home and saw a chance to end the hypocrisy. He allied with Hawaiian labor unions and this guy, Jack Burns, to kick start a movement that would bring democracy to the islands. And in 1959, Hawaii became a US state, with equal legal rights and universal suffrage.[2]

For the time being, ‘Iolani Palace remained the Capitol of this new state, but to Burns, that didn’t seem right. Sure, a democracy shouldn’t be run from a palace, but also Hawaii had just changed too much. The islands needed a new Capitol. So, when Burns became governor a few years later, he set to work, but this building would be different, unlike any other in America. And in 1969, when Burns dedicated the completed building, it was.[3]

Composed of lines, planes, and open spaces, the building borrowed…borrows heavily from the Bauhaus-inspired International architectural style, which originated in Europe decades prior. But Burns also wanted a distinctly Hawaiian twist. So, let’s talk about those columns, moat, atrium, and more. Just as the Pacific surrounds these islands, this building is wrapped with a reflecting pool moat. At the back and front of the building, just behind me, there are 8 columns for the 8 islands of Hawaii, each designed to mimic the royal palm. Here, from the side of the building, you can see the conical legislative chambers, shaped like the volcanoes that made these islands, while around the building you can find four kukui nut trees: the state tree of Hawaii, and a sacred number for the four major Hawaiian gods. And, of course, there’s this gorgeous atrium—no dome but the sky, and this artistic centerpiece to literally reflect it.[4]

The islands, the sea, the sky, and the native religion — all these things are represented here. But does it represent Hawaii?

This building embodies one narrative, perhaps the most common narrative, of the Hawaiian experience—one that confronts the legacy of oppression, violence, and imperialism in Hawaii’s past, and stakes its claim on the future being different. Hawaii is fully democratic today, and it does place a special emphasis on native Hawaiians’ and their struggles, with the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, a kind of fourth branch of government devoted to the needs and voices of native Hawaiians.[5] And the Hawaiian language has a special role in both the government and culture of the state, in a way hardly seen anywhere else in America.[6]

But many question this narrative. They believe that the government of Hawaii remains illegitimate, that statehood is just an entrenchment of the injustices of annexation and exploitation, and understandably so. To them, Hawaii isn’t a state; it’s an illegally occupied territory. The Capitol building may be cleverly designed, but what it represents isn’t Hawaii but subjugation.[7]

And maybe the story that the capitol tells isn’t perfect. There is more to be done to right the wrongs of the past. But the clock can’t be turned back—identities change, and Hawaii, right in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, has a hemispheric multicultural inheritance. Traditions have been invented and reshaped, even as we continue to treasure them. The Hawaiian capitol, for whatever flaws we can identify in the narrative it embodies, is actually a really powerful symbol of this marriage of the past, present, and future: a bold and, I think, hopeful answer to the question “what is Hawaii?”

Notes

- Phil Barnes, A Concise History of the Hawaiian Islands (Petroglyph Press: Hilo, 1996), 38-54. ↩︎

- Ibid., 62-70. ↩︎

- Dan Boylan and T. Michael Holmes, John A. Burns: The Man and His Times (University of Hawaii Press, 2000). ↩︎

- Cheryl Chee Tsutsumi, “State Capitol Awash with Meaning,” for the Historic Hawaii Foundation, 18 January 2018. ↩︎

- Office of Hawaiian Affairs, “About.” ↩︎

- University of Hawaii, “About the Hawaiian Language.” ↩︎

- Aislyn Greene, “What is the Hawaii Sovereignty Movement,” in AFAR, 2 September 2021. ↩︎

Comments

Join the conversation