The Briefing: Brexit is alive and well.

- An election recap

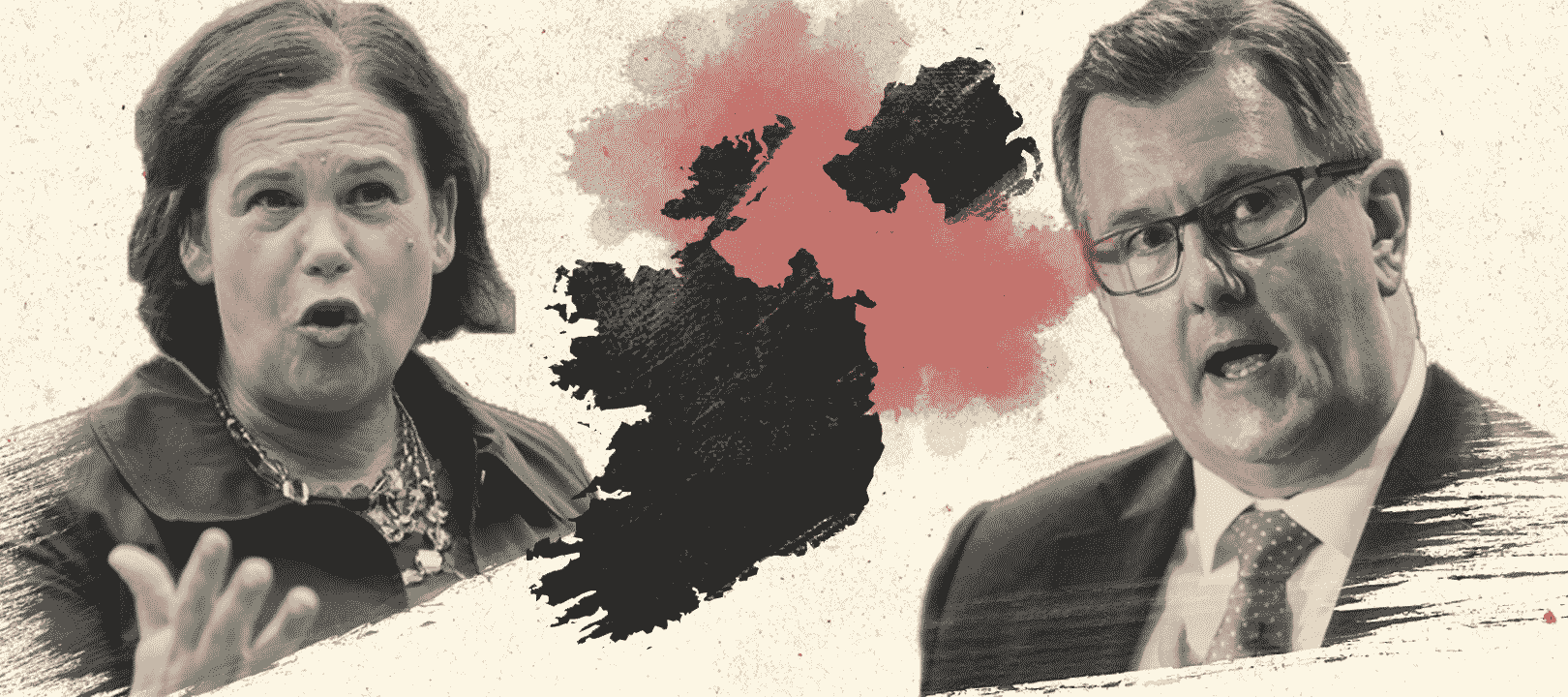

- Northern Irish politics are defined by competition between pro-Irish-unity "nationalists" and pro-UK "unionists"

- The country (and part of the United Kingdom) is predominantly Protestant and unionist by design

- But last week, the nationalist Sinn Fein party won the most seats for the first time

- Last week's Insight — the difficulties of power-sharing

- Get the full story here, if you missed it

- Northern Ireland has only seen consistent peace since the late 1990s

- The Good Friday Agreement (1998) established a power-sharing arrangement between unionists and nationalists

- Today, the leading unionist party is blocking Sinn Fein from forming a government

- Unionists are demanding reform of the Northern Ireland Protocol which "solved" Brexit

- Where things stand

- In typical fashion, Boris Johnson's government seems all bluster and no bite

- The EU offered to open negotiations into reforming the protocol

- Johnson's Foreign Secretary, Liz Truss, rejected the proposal and suggested the UK may move ahead unilaterally, which could trigger a trade war with the EU

- Yesterday, Truss wavered, promising not to scrap but improve the protocol

The Big Question: What’s the big deal?

The Irish border challenge and the difficulties posed by Brexit deserve a brief explanation. In addition to the power-sharing arrangement that I wrote about last week, the Good Friday Agreement also satisfied both unionists’ and nationalists’ desires for open borders. Unionists wanted to maintain their open border with the rest of the United Kingdom (UK), while nationalists desired one with the Republic of Ireland (ROI).

Both countries were also part of the European Union, which guarantees the free flow of goods in addition to people across member states. As long as both the ROI and UK remained in the EU, the EU’s lack of internal borders served to reinforce the open-borders provision of the Good Friday Agreement. However, when the UK voted to leave the EU in 2016, the free movement of goods and people between the UK and the EU—including the ROI—couldn’t continue.

Solving this puzzle was perhaps the largest challenge of the entire Brexit negotiation process, and the eventual solution became known as the Northern Ireland Protocol. Instead of re-establishing a land border between the ROI and NI and risking renewed violence on the island, Johnson’s government set up a maritime customs border border between NI and the UK.

So here’s the problem. Unionists in Northern Ireland are chafing at apparent divisions between themselves and the rest of the United Kingdom, but nationalists can’t countenance a border with the Republic of Ireland.

As is made clear by the current political standoff between Sinn Fein and the unionists, for Irish politics to work, both sides need to get their way. As long as the UK is out of the EU and the ROI is in it, however, that looks impossible. A border needs to be enforced somewhere.

The Theory: “Institutional complementarity.”

In the field of political economy—which studies how political and economic systems interact with and influence each other—there’s a theory known as “institutional complementarity.” It goes something like this; certain political institutions and economic institutions, though separate, can either complement and support each other or be at odds.

Though the term wasn’t coined, as far as I can tell, until the ‘90s, it’s obviously central to liberal democracy. After all, that’s about a perfect description of how liberal theorists thought of capitalism and democracy as mutually reinforcing. For example, take private property (an economic institution) and independent courts of law (a political institution). These separate political and economic institutions are complementary and mutually-reinforcing. Independent courts help protect people and their property from especially rapacious political officials, while private property helps bolster the courts’ independence by inhibiting the consolidation of wealth and power by overly-ambitious office-holders.

In the case of Northern Ireland and the EU, there was a similar situation of complementary institutions. The EU’s removal of internal borders in 1993 paved the way for the Good Friday Agreement to follow suit by 1998. However, with the UK’s departure, the EU’s economic institution of ‘no internal customs borders’ is now at odds with the UK’s political functioning.

The Takeaway: Not what we want but what we have.

In some ways the lesson of institutional complementarity theory is rather familiar, maybe even banal. Certain political and economic institutions work well together, while others don’t. Everyone knows that on some level, whether or not everyone knows the name of the theory.

But in the case of the UK and the ROI, it’s a potentially deadly reality, not an abstract concept. Northern Ireland exists at a nexus of three institutions—the Good Friday Agreement, the UK, and the EU. When all three were aligned, institutional complementarity produced a democratically legitimate political settlement, peace between warring factions, and positive-sum economic gains. Now that those three institutions are no longer aligned, however, they’ve created an entanglement that threatens all of those considerable benefits.

Indeed, it’s important to remember complementarity with these sorts of big picture situations, but it’s also applicable to day-to-day policy questions. Instead of only thinking about whether civil liberties can survive in a command economy, or whether the Chinese model of free-ish markets and tight government control is sustainable, we might do well to consider complementarity when talking about different tax or education or healthcare policies—how these things are likely to interact with our existing rules and institutions. If British voters in 2016 had done so, Irish peace might not be so tenuous today.

Subscribe to Spectacles

Be sure to check out our last piece on the situation in Northern Ireland

Comments

Join the conversation